NKVD Gulag Officer ID Book

(Click

on image to enlarge)

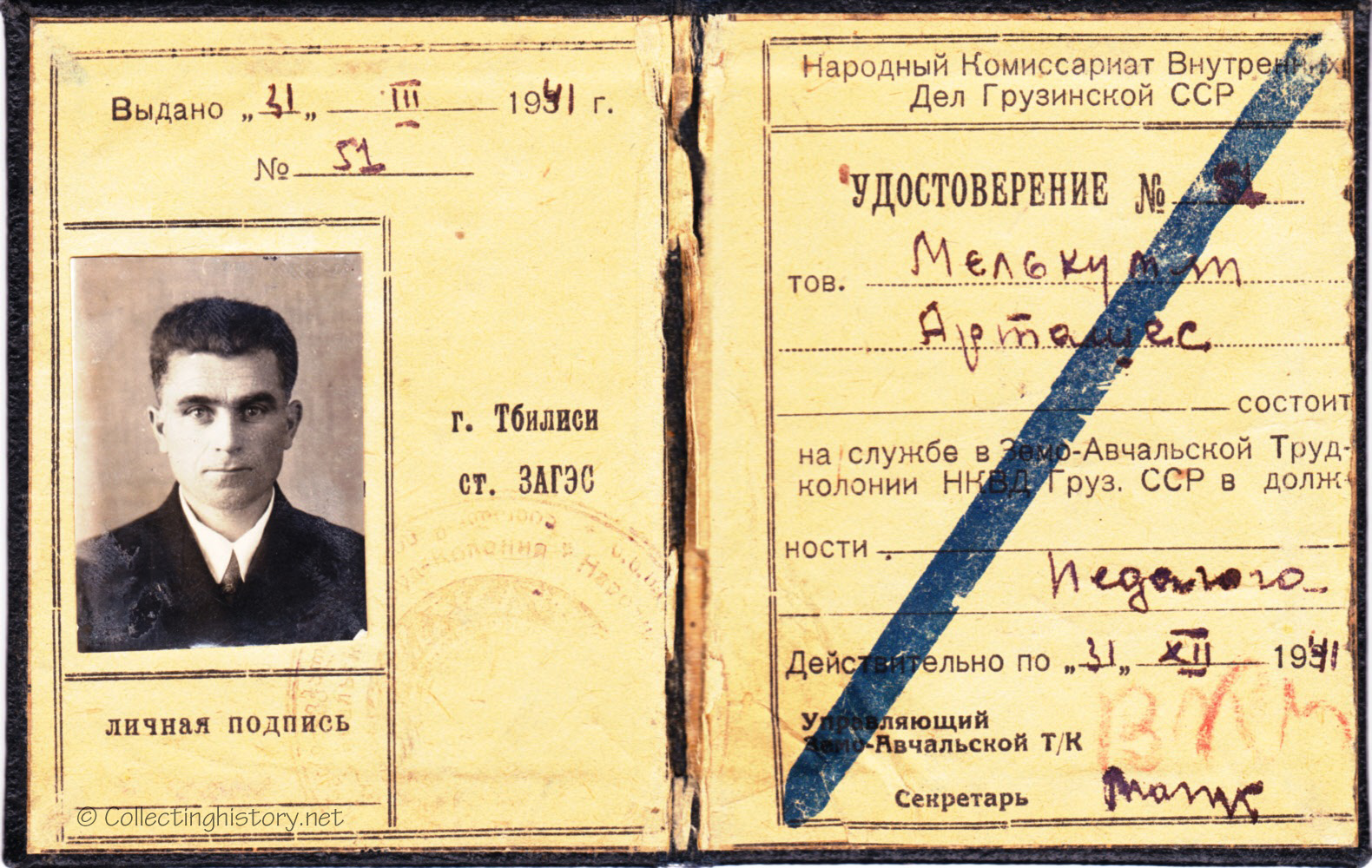

This is an original NKVD (precursor to the KGB), black ID book for an officer in a Soviet labor camp. The cover states "NKVD - ZEMO-AVCHALSKI LABOR CAMP."

These interior pages have a photo of the officer (in civilian dress) and state, "Peoples Commisariat of Internal Affairs of Georgian SSR certifies that Malkumt Artashes is an instructor of labor camp." The serial number is quite low, No. 51. It was issued 31 March 1941, and expired 31 December 1941. This officer could very well have been one of the individuals responsible for the deaths of millions of people.

Black IDs (as opposed to red ones) were issued to GULAG officers only. Regarding his role as "instructor," this could mean anything from a simple teacher of Russian literature for poor prisoners, to a supervisor, who controlled everything, spied on the camp personnel and tortured people. The low serial number could indicate that the latter is true.

Serial numbers in Soviet Russia were very important amongst party elite. Typically Soviet labor camps were huge, with many hundreds of guards and other personnel, so #51 would be important. This individual could be one of those who spied on his own supervisor, hoping to take his place. His role, besides his immediate functions, could be looking for treason and reporting the suspected.

What possibly could have been his involvement in the deaths? If the above is true then most direct. An individual like this had to set an example of how to treat "enemies of the people."

The Soviet Secret Police

From the beginning of their regime, the Bolsheviks relied on a strong secret, or political, police to buttress their rule. The first secret police, called the Cheka, was established in December 1917 as a temporary institution to be abolished once Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks had consolidated their power. The original Cheka, headed by Feliks Dzerzhinskii, was empowered only to investigate "counterrevolutionary" crimes. But it soon acquired powers of summary justice and began a campaign of terror against the propertied classes and enemies of Bolshevism. Although many Bolsheviks viewed the Cheka with repugnance and spoke out against its excesses, its continued existence was seen as crucial to the survival of the new regime.Once the Civil War (1918-21) ended and the threat of domestic and foreign opposition had receded, the Cheka was disbanded. Its functions were transferred in 1922 to the State Political Directorate, or GPU, which was initially less powerful than its predecessor. Repression against the population lessened. But under party leader Joseph Stalin, the secret police again acquired vast punitive powers and in 1934 was renamed the People's Comissariat for Internal Affairs, or NKVD. No longer subject to party control or restricted by law, the NKVD became a direct instrument of Stalin for use against the party and the country during the Great Terror of the 1930s.

The secret police remained the most powerful and feared Soviet institution throughout the Stalinist period. Although the post-Stalin secret police, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti, Committee for State Security), no longer inflicted such large-scale purges, terror, and forced depopulation on the peoples of the Soviet Union, it continued to be used by the Kremlin leadership to suppress political and religious dissent. The head of the KGB was a key figure in resisting the democratization of the late 1980s and in organizing the attempted putsch of August 1991.

The KGB controlled both the political and federal police and the intelligence and counterintelligence activities of the USSR. It policed Soviet borders, operated prison camps and mental hospitals, and directed a large network of internal informers. At the end of the Soviet period it was estimated to have between 400,000 and 700,000 people on its payroll. Founded in 1954, the KGB succeeded the NKVD and the MGB (1946). In the late 1980s, the KGB became one of the main centers of resistance to the movement for reform and democratization initiated by Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev.

After the breakup of the USSR, the role of the KGB was at first severely restricted by the Russian government. In 1995, however, it was renamed the Federal Security Service, given broad authority to combat crime and corruption, and entrusted with the task of providing security for the government and the armed forces.

The

GULAG

The Soviet system of forced labor camps was first established in 1919 under the Cheka, but it was not until the early 1930s that the camp population reached significant numbers. By 1934 the GULAG, or Main Directorate for Corrective Labor Camps, then under the Cheka's successor organization the NKVD, had several million inmates. Prisoners included murderers, thieves, and other common criminals--along with political and religious dissenters. The GULAG, whose camps were located mainly in remote regions of Siberia and the Far North, made significant contributions to the Soviet economy in the period of Joseph Stalin. GULAG prisoners constructed the White Sea-Baltic Canal, the Moscow-Volga Canal, the Baikal-Amur main railroad line, numerous hydroelectric stations, and strategic roads and industrial enterprises in remote regions. GULAG manpower was also used for much of the country's lumbering and for the mining of coal, copper, and gold.

Stalin constantly increased the number of projects assigned to the NKVD, which led to an increasing reliance on its labor. The GULAG also served as a source of workers for economic projects independent of the NKVD, which contracted its prisoners out to various economic enterprises.

Conditions in the camps were extremely harsh. Prisoners received inadequate food rations and insufficient clothing, which made it difficult to endure the severe weather and the long working hours; sometimes the inmates were physically abused by camp guards. As a result, the death rate from exhaustion and disease in the camps was high. After Stalin died in 1953, the GULAG population was reduced significantly, and conditions for inmates somewhat improved. Forced labor camps continued to exist, although on a small scale, into the Gorbachev period, and the government even opened some camps to scrutiny by journalists and human rights activists. With the advance of democratization, political prisoners and prisoners of conscience all but disappeared from the camps.

(Document translation and some text courtesy of Alexei Merezhko)

(Some text courtesy of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Grolier's Encyclopedia)